A 7.5-meter (25-foot) dugout canoe was made using replicas of ancient stone tools.

Researchers have explored how early modern humans migrated by sea from Taiwan to southern Japan approximately 30,000 years ago.

To unravel the mysteries of these difficult ancient voyages, the researchers employed a unique combination of numerical simulations and experimental archaeology.

Interestingly, researchers from Japan and Taiwan, led by Professor Yousuke Kaifu of the University of Tokyo, recreated a 30,000-year-old sea crossing.

The team set out in their handmade canoe, making the entire experience as authentic as possible.

For this, a 25-foot (7.5-meter) dugout canoe was made using replicas of ancient stone tools. The canoe was paddled about 140 miles (225 kilometers) across the open ocean, connecting eastern Taiwan to Yonaguni Island in Japan’s Ryukyu group.

Building a real boat

How early human populations navigated the seas between islands like Taiwan and Southern Japan has remained a captivating mystery.

“We initiated this project with simple questions: ‘How did Paleolithic people arrive at such remote islands as Okinawa?’ ‘How difficult was their journey?’ ‘And what tools and strategies did they use?’” said Kaifu.

“Archaeological evidence such as remains and artifacts can’t paint a full picture as the nature of the sea is that it washes such things away. So, we turned to the idea of experimental archaeology, in a similar vein to the Kon-Tiki expedition of 1947 by Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl,” the author added.

One paper used numerical simulations to test navigating the strong Kuroshio Current. The simulation revealed that skillful boat-making and navigation could overcome the Kuroshio Current even with ancient tools.

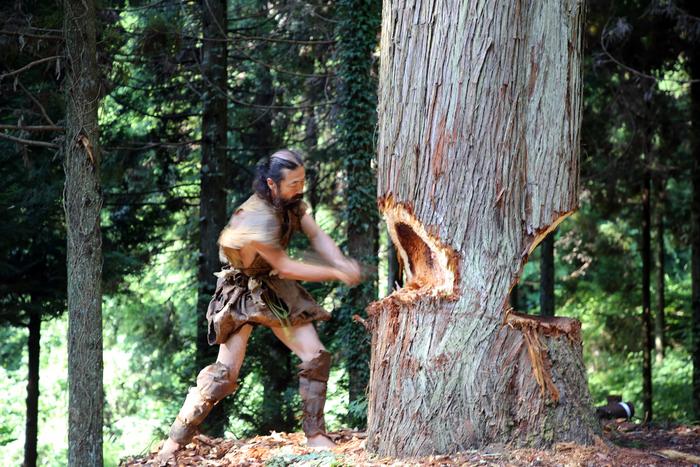

The other paper detailed the heart of their experiment: building a real boat or canoe dubbed “Sugime.” In 2019, they reportedly built a dugout canoe from a Japanese cedar trunk, using replicas of 30,000-year-old stone tools.

Paddling for 45 hours

The canoe was paddled in the Ryukyu group from eastern Taiwan to Yonaguni Island.

For over 45 hours, they navigated the open sea, often with their destination out of sight, relying solely on the sun, stars, swells, and their instincts.

The team initially theorized that ancient people used rafts for sea crossings.

However, experiments showcased that rafts were too slow and lacked the durability to work against the ocean currents. In contrast, the dugout canoe proved to be both “fast and robust.”

“We now know that these canoes are fast and durable enough to make the crossing, but that’s only half the story. Those male and female pioneers must have all been experienced paddlers with effective strategies and a strong will to explore the unknown,” said Kaifu.

“We do not think a return journey was possible. If you have a map and know the flow pattern of the Kuroshio, you can plan a return journey, but such things probably did not take place until much later in history,” Kaifu added.

The team also ran hundreds of virtual voyages using advanced ocean models to fill in the gaps that a single experiment couldn’t.

The simulations explored different starting locations, seasons, and paddling approaches, considering current and historical ocean conditions.

The research found various insights into ancient seafaring strategies: starting from northern Taiwan increased the chances of a successful crossing.

RECOMMENDED ARTICLES

Furthermore, a key tactic was to paddle slightly southeast instead of directly towards the destination. This subtle but vital adjustment was essential for compensating against the powerful Kuroshio Current.

These findings suggest that our ancestors had a remarkably sophisticated understanding of ocean dynamics and navigation.

The findings were detailed in two papers published in the journal Science Advances on June 25.